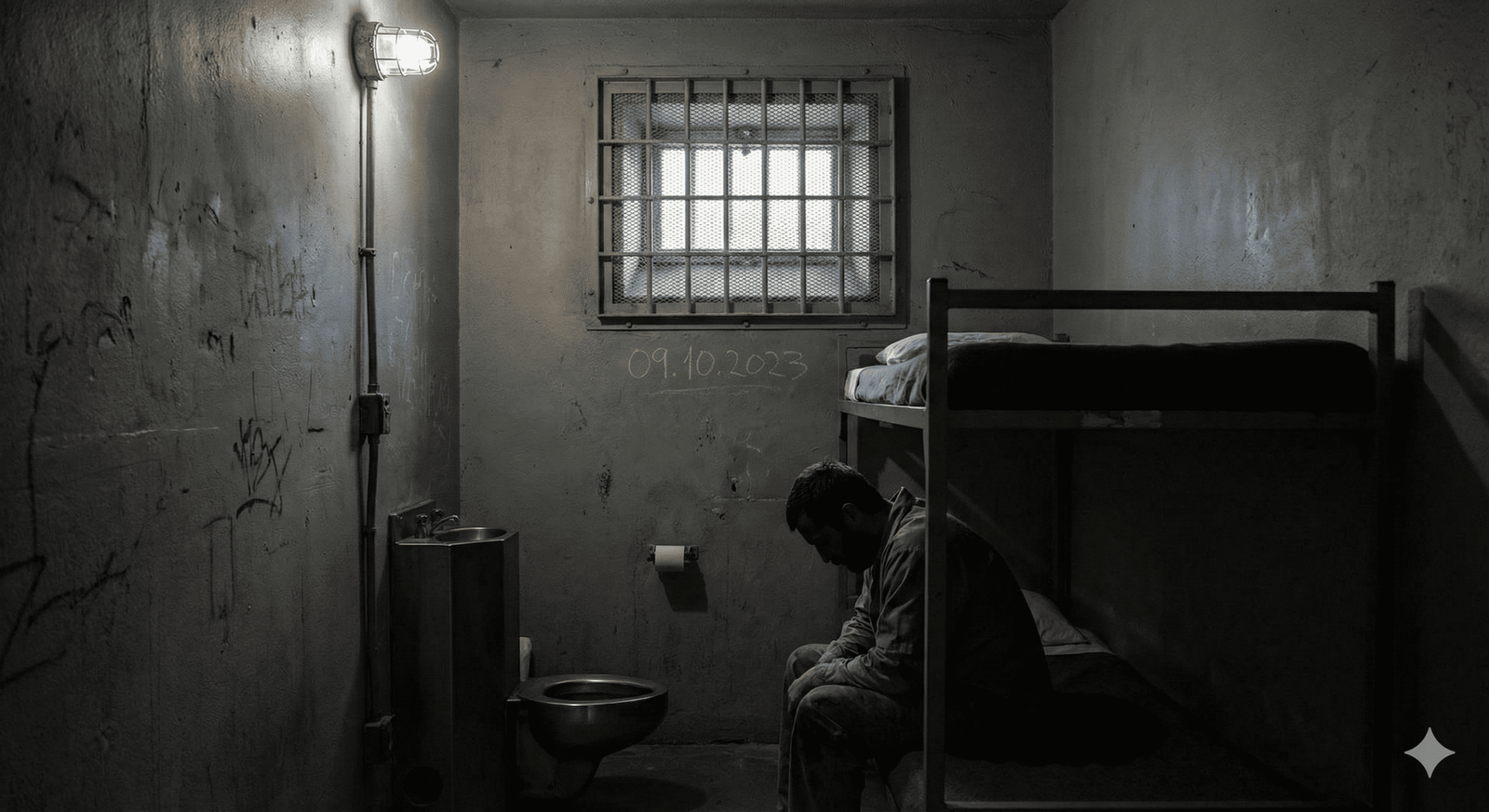

“These places are graves for living humans,” says Serkan Onur Yılmaz, a former inmate of one of Turkey’s new high-security prisons.

Introduced in 2021, they have been labelled “well-type prisons” by inmates and human rights advocates – who compare incarceration in such structures to being stuck at the bottom of a well.

“[My cell] didn’t get any sun,” says Ali Hasan Akgül, another former inmate. “You got maybe a single ray if you were lucky. It’s not possible to look out the window, it has three layers of screens over it. Not even a mosquito could get in. It’s like you’re inside a cage.”

Yılmaz and Akgül, who were confined to well-type prisons until last summer, are among dozens of inmates who have staged hunger strikes to demand an end to extreme isolation and round-the-clock surveillance.

“They watched us sleep, eat, sit around,” says Akgül. “They monitored how many minutes we spent on the toilet, when we bathed, everything.”

Even speaking to the guard requires pressing a button for a radio transmitter, Akgül says, arguing that “the human psyche is not suited for well-type prisons”.

“Either you go mad in there, or you have to resist.”

Credit: Generated by using Gemini

Too many prisoners

Turkey’s prison system is full to bursting. In October 2025, according to a report by the Civil Society in the Penal System Association (CISST), prisoner numbers were 38% above capacity, with more than 420,000 inmates.

In January, the international NGO Human Rights Watch published a report listing overcrowded prison facilities, politicised trials and the widespread and arbitrary use of anti-terrorism legislation as key problems in Turkey’s justice system.

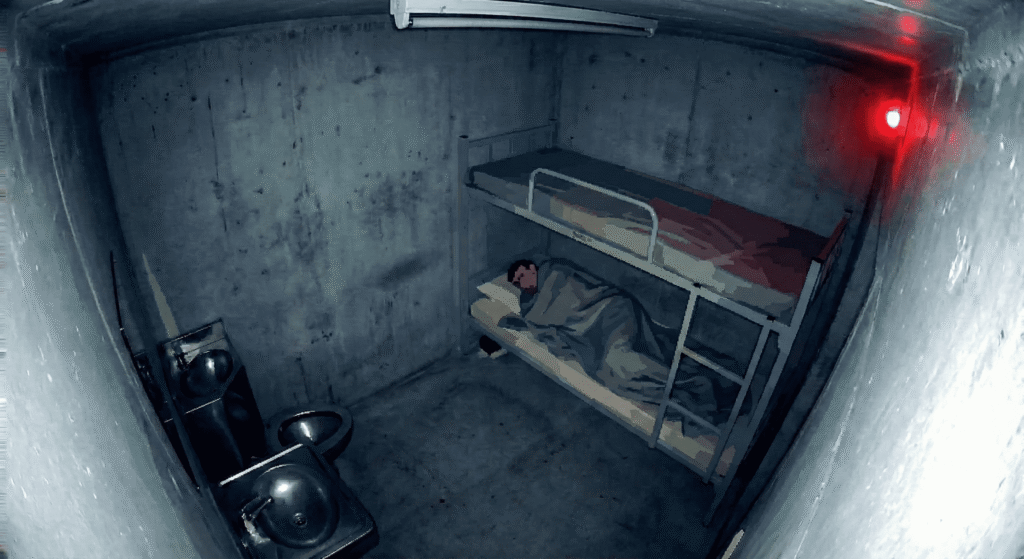

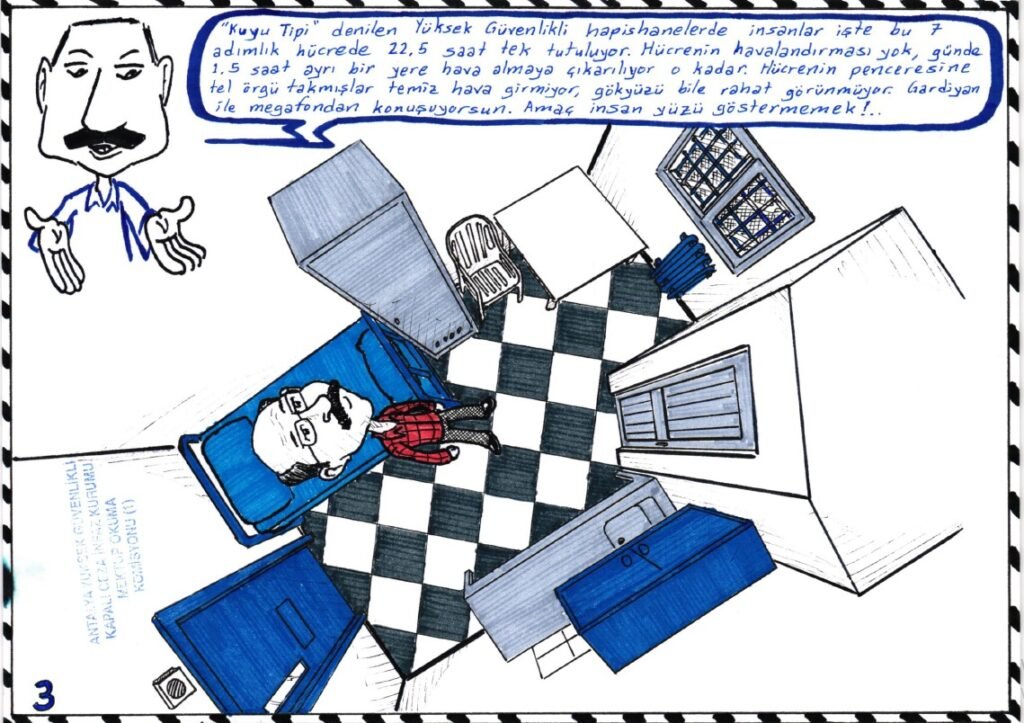

Well-type prisons, built to expand Turkey’s prison capacity, confine inmates to their cells for 22 to 23 hours a day. The cells are approximately five square-metres large, including a kitchen, a toilet and a bed, spaces designed to allow inmates to take only a few steps.

Turkey’s justice ministry argues that the institutions are designed for high-risk inmates, and prisoners who attempt escape or incite riots. Human rights defenders say they’re also used to confine political prisoners.

Mehmet Pehlivan, a lawyer for the jailed mayor of Istanbul Ekrem İmamoğlu – widely seen as president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s main political rival – is currently being held in a well-type prison in Çorlu, western Turkey.

With screens and railings over windows, well-type cells do not receive direct sunlight and rarely have a view of the sky. Inmates track the time of day not with the movements of the sun, but according to when cell doors are opened and closed.

Credit: Generated by using Gemini

Communication is also seriously limited. Letters are censored. Phone calls are short, rare and closely monitored.

After 213 days spent in a well-type prison, Yılmaz describes them as “an attempt to ensure a person’s submission through isolation”. After spending a majority of the day alone in a cell, Yılmaz says, one loses their perception of time.

Transfers to well-type prisons are often sudden and carried out without informing inmates’ families, according to family members who usually find out their loved ones’ location when it’s already too late.

Only short visits are allowed, with prisoners separated from their relatives by reinforced glass.

Akgül and Yılmaz’s stories match the testimonies in letters sent from other well-type prisons.

“Being held here feels like being kept in a cage,” says İskan Özlü, an inmate at the western Burdur High-Security Prison.

Talat Şanlı, an inmate at the eastern Van High-Security Prison, says that their rights to medical treatment and communication are systematically violated.

An ill prisoner, Mahsum Yüksekdağ says he was not able to receive treatment for a brain aneurysm because he refused to be examined in handcuffs.

“I don’t want to die young but I won’t accept undignified treatment,” he says.

“Psychological torture”

Rights organisations have criticised the use of well-type prisons, arguing that the single-person cells, lack of communal spaces and constant surveillance make human interaction impossible.

A 2025 report by Turkey’s Human Rights Association (İHD) describes how inmates are put in a single-person line when they are taken out of their cells for visits or exercise, and are banned from talking to one another. Cameras in their cells are reported to view the whole space, including the bathroom.

The Turkey Human Rights Foundation (TİHV) describes such practices as “emotional deprivation” and “psychological torture”. The European Council Committee to Prevent Torture (CPT) warns that long-term isolation risks inflicting serious psychological damage, and argues that it cannot be practiced indefinitely, even for security reasons.

In response to these claims, the Justice Ministry told Inside Turkey that high-security prisons were designed in accordance with human dignity. The Ministry also claimed that conditions in Turkish prisons were better than those in Europe.

Emir Karakum, from the Association for Solidarity of Inmates’ and Convicts’ Families (TAYAD), says well-type prisons use technology as well as architecture to impose isolation.

“The goal is to make sure inmates see as few people as possible,” Karakum says, noting that these prisons use American-style electronic doors. “Communication is cut off from the start, inmates cannot communicate with other prisoners or guards directly.”

Karakum also argues that the screens on the windows, preventing sunlight from entering, are also deliberate choices.

“They want to prevent inmates from seeing the sky,” he says.

Warning against the potential heavy psychological and neurological consequences well-type prisons could have, neurology expert Hakan Gürvit says long-term solitary confinement increases the risk of depression and suicide.

“Those who started the well-type prison model will go down in this country’s history of evil,” Gürvit says.