It’s a new school year in Turkey, but for thousands of children that means going to lessons hungry. With around 29.3% of Turkey’s population at risk of poverty – and free school meals still not an option for most children, despite having been debated by politicians for years – malnutrition is a pressing issue.

“My daughter has lost so much weight in the last two years because of malnutrition,” one mother, who asked not to be named, tells Inside Turkey. “Even though she didn’t really want to, she even considered wearing a hijab and dressing conservative to hide how skinny she has gotten. Just because she was worried people would mock her skinniness.”

According to the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK), children make up the largest group among those at risk of poverty. Almost one in four children in Turkey do not eat red meat, chicken or fish regularly, while one in ten don’t eat fresh fruit or vegetables daily.

Limited support

Yeliz, a single mother who lives in Ankara’s Mamak district, has two children: one who started university this year, and one who started primary school. At the moment, because of childcare demands, she can only work at weekends, as a waitress.

“Food aid is crucial to me because it’s really expensive to put together a home-cooked meal,” Yeliz says, adding that she can only put meat on the table thanks to benefit payments from her local municipality.

“We can buy chicken with the 600 lira [around $12] we receive from Ankara Metropolitan Municipality monthly,” she says, explaining that she can’t ever afford to buy red meat – and only eats it rarely, during holidays, when relatives sacrifice an animal.

Across Turkey, municipalities try to supplement the incomes of poorer families, but there is no systematic, centralised programme.

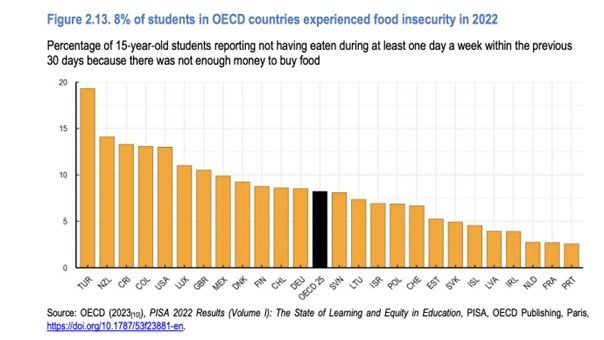

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD), 20% of pupils below the age of 15 in Turkey skip meals at least one day a week; the highest rate among the countries surveyed.

Other parents have it worse. “Some days I don’t eat so that my children can have more to eat,” says a mother of five, a cleaner by profession, who asked to remain anonymous.

“But how much nutrition can they get from pasta with yoghurt? Sometimes I’ll bring home leftover cheese or yoghurt from the rooms I clean [small packages of cheese offered in hotel breakfasts]. That is the only way my children can have something besides pasta. Some days there’s nothing to eat and we all spend the day without food.”

Back to school blues

Hacer Foggo, founder of the Deep Poverty Network charity, says she has been receiving phone calls from all over the country asking for help at the start of the school year. Most often, it’s mothers calling.

“I have worked in the field of poverty for 20 years. It is always women you see outside of social aid centres, municipalities,” Foggo says.

She adds that not being able to put enough food in their children’s lunchboxes is the biggest problem faced by low-income mothers. Uniforms and stationery costs follow.

Credit: CHP

Echoing Foggo’s observation, a teacher in Diyarbakir, south-eastern Turkey, says it is common for pupils at their school to skip breakfast.

“The poverty prevents the children from having healthy nutrition,” says the teacher, whose name is being withheld because they are a public servant and not authorised to speak to the media. “Most of their lunchboxes only contain bread, tomatoes or simple cheese. Most of them are skinny.”

Menekşe Tokyay, a journalist and the author of “Karnım Zil Çalıyor” (“My Stomach Bells are Ringing”, a Turkish phrase that expresses hunger), says that child poverty is “a reality of society in Turkey”. She has gathered accounts of children chewing gum or drinking water from school fountains to suppress their hunger, or hiding themselves away at lunch breaks because their lunchboxes are empty.

Credit: Her own archive

More support would not just improve children’s health but also secure their right to education, Tokyay adds.

“School meals are a great motivation for families to send their children to school, especially in low-income areas,” Tokyay says. “This reduces pupils’ absences, child labour and underage forced marriages.”

Credit: Menekşe Tokyay’s archive & İletişim publishing

A chance to eat

Comprehensive free school meals have been on the government’s agenda for a long time, but are yet to be introduced. Currently, school meals are offered only to pupils who attend schools outside of their area of residence and pre-school pupils affected by the earthquakes in southern Turkey in 2023.

The Education Ministry provided free meals to 1.4 million students in 2022 and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said this number would be increased to five million. However, the project was suspended in the school year 2023-2024.

Globally, the picture is different. According to data from the School Meals Coalition, a UN initiative, 466 million children worldwide eat for free at school every day. Countries like India, Brazil and Finland reserve a significant portion of their state budget for school meal programmes.

Yeliz, the single mother from Ankara, would like to see a similar effort in Turkey. “This way, all children would get a chance to eat,” she says.

“Look at the prices of breakfast foods. When my son sees his friends eating sausage at school, he asks me for some. I can’t keep up.”

School costs, she adds, are not limited to the lunchbox.

“This affects people psychologically as well,” says Yeliz. “Imagine not being able to afford [basic] things for your children. I know a lot of women who suffer from depression because of this.”